The holiday season is fast approaching, organized sports are coming to a halt, work is winding up and many of us are embarking upon holidays. The Christmas break is a time where we are often given the opportunity to reconnect with friends and family while having a break from a regular schedule. While this opportunity to recharge may be necessary, it can also be to the detriment of any fitness progress and goals you have achieved throughout the passing year. Fitness loss is commonplace, not only during the Christmas holidays but during any extended period of reduced physical activity and we often refer to this effect as detraining.

Detraining and the Residual Training Effect:

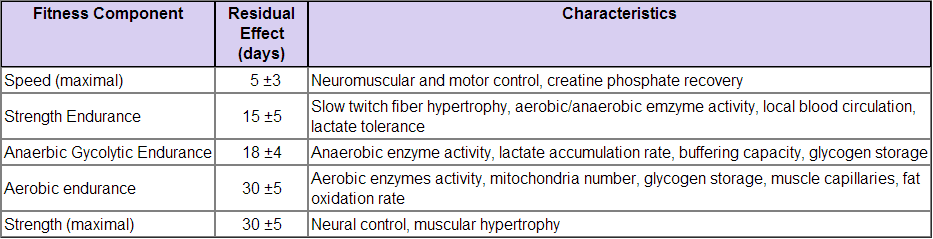

Lets talk about detraining, you may have heard about it somewhere along the grapevine or maybe you have had first-hand experience with it, most likely the latter. The relationship between detraining and the residual training effect revolves around the idea that after cessation of training or an acute reduction in volume the body begins physiological processes which slowly untie any positive adaptations to training we may have made (detraining/deconditioning). It is these physiological characteristics that when grouped together make up what we call fitness components. These components include speed, maximal strength, aerobic endurance, strength endurance and anaerobic endurance. Now, while these may not all relate to you, there are most likely one or two which are inclusive in your fitness goals (no matter how basic or specific they are).

However, it may not be all doom and gloom. It is important to know that not all of these characteristics deteriorate at the same rate, some are much more resilient to detraining than others.

The table below gives an outline of how long the physiological adaptations are maintained during a period of detraining.

The Residual Training Effect

What effects the residual training effect?

- Duration of training before reduction or cessation

- Training age and physical experience

- Intensity used during the detraining period (moderate to high-intensity exercise reduces rate)

You may be asking “how does this relate to me?”

As shown in the table above we can see that speed is the most susceptible to change (2-8 days), whereas maximal strength and aerobic endurance are the most resilient (25-35 days). If your goals are to maintain speed and strength endurance it would be counterproductive to completely stop training, these components would best be maintained with a few short sprint and full body hypertrophy sessions during the break. Whereas if your goals are to maintain maximum strength and aerobic endurance; While it would not be ideal to completely stop training, the reduction in training volume would not have such a detrimental effect as the components mentioned previously.

So what should you take out of this?

- Try to integrate some moderate to high-intensity training into your break to slow down these detraining effects.

- Short sessions with a focus on the components that are most susceptible to change or relate closest to goals are recommended.

- Sports where repeated sprint ability (RSA) is critical to performance (AFL, Soccer, Basketball), should focus training on sport-specific needs for the athlete and include short sprint sessions. There is not a great need to prescribe or complete long aerobic/anaerobic endurance sessions during the break where time is often scarce.

- Reflect on your current and previous goals and how this concept relates to you if you are planning on taking a break.

Would you like to re-assess your health behaviours and identify what you need to work toward over the coming year?

Our scorecard is a quick and simple questionnaire to help you do this.

Take The Scorecard Here

It’s free and only takes 7 minutes

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

0 Comments